South Devon Railway

Totnes

In which Joe finds not only an engine house but a castle.

Explorations: 25 June 2018.

Journey: Paddington to Totnes.

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Paul Garnsworthy, editor, Brunel's Atmospheric Railway, The Broad Gauge Society, 2013.

- Peter Kay, Exeter–Newton Abbot: a Railway History, Platform 5, 1991, and excerpts in Garnsworthy.

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- G.A. Sekon, A History of the Great Western Railway, Digby, Long, 1895.

The tenth engine house on the South Devon Railway was in Totnes. The engine house proper and the boiler house still stand. Only the chimney is missing, although it was still present in a photograph dated 1937. By the summer of 1848 the 22-inch pipe was laid as far as Totnes, and the engine house buildings were ready for the installation of machinery, which was begun but not completed because of the Board's decision to abandon atmospheric power. Instead of a reservoir tank, water was probably to be taken from the River Dart, as it was from the Exe in Exeter.

If it had been activated, Totnes engine house would have had the easiest job of all of them, because in both directions, approaching trains were coming down steep grades and would have arrived by mainly by gravity.

— Totnes, Ordnance Survey 25-inch, 1890. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 courtesy National Library of Scotland.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan.

The Totnes railway property was just south of the River Dart and a secondary parallel water called the Mill Leat. The map shows a Goods Shed that lasted well into the twentieth century. Its stone foundation now supports the farthest part of the car park. From there visitors can walk on a public footpath and footbridges to reach the Totnes Riverside terminus of the heritage South Devon Railway and next to it the Totnes Rare Breeds Farm. The track seen here on the right was the Totnes Quay branch for freight.

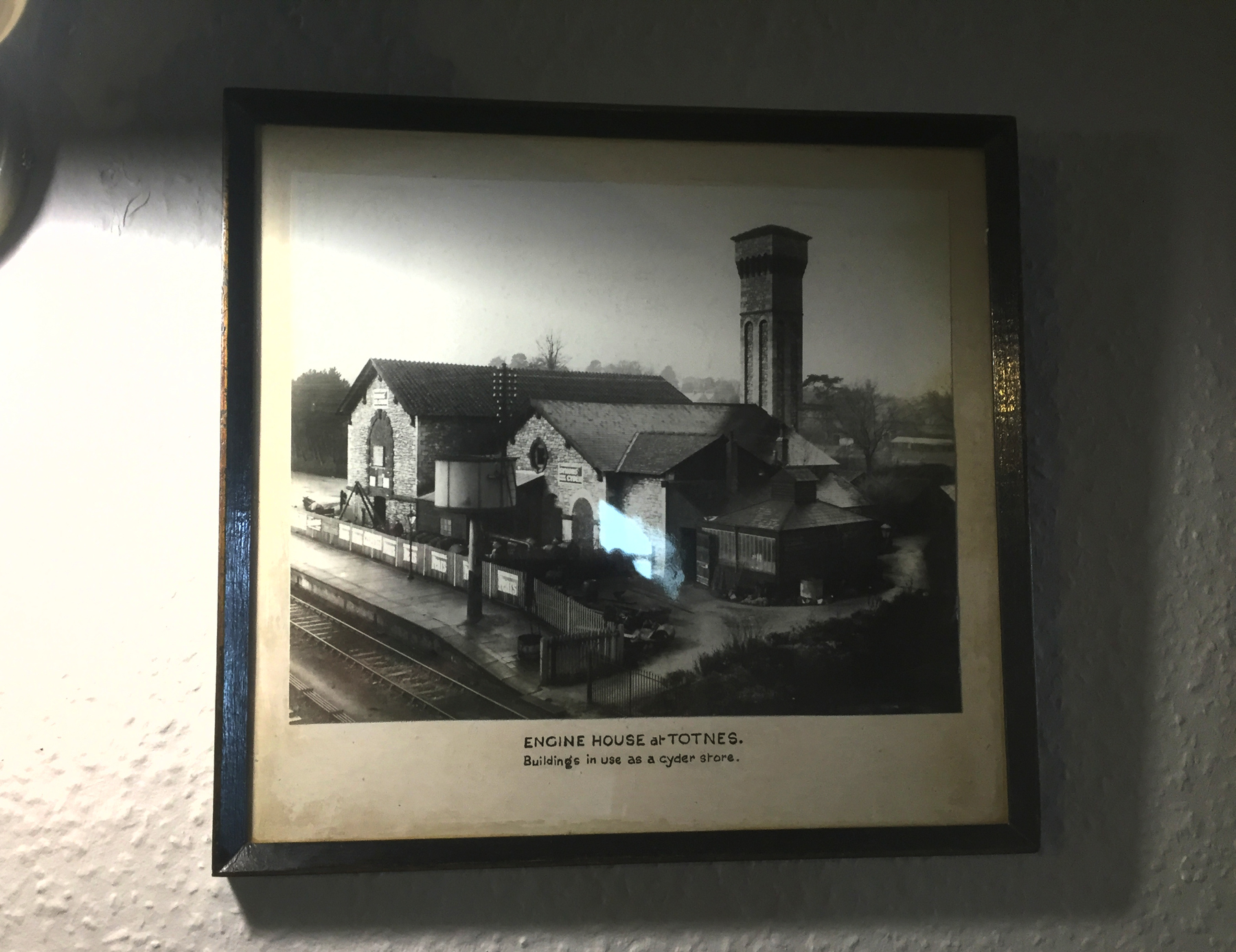

An undated photograph that hangs on the wall of The Atmospheric Railway in Starcross shows where the chimney was. Some additions to the boiler house seen here were later removed.

— "Engine House at Totnes. Buildings in use as a cyder store." The Atmospheric Railway, Starcross.

The buildings were used from 1934 to 2007 by a series of creamery companies, with quite appropriately two gigantic horizontal boilers in the boiler house, which were however connected to a new cylindrical chimney. In 1966 the creamery reportedly produced a ton of Devon clotted cream each day! The last user, Dairy Crest Creamery, sold the buildings in 2014 to a community group for the price of 1 Totnes Pound, a local currency that is accepted for £1 at businesses in town. English Heritage has given the atmospheric buildings a Grade II listing.

Below are two of my photographs showing the buildings looking quite well by 2018, with new roofs and a new window on the engine house where it had been bricked up. On the left is the Signal Box Cafe, which served its original purpose from 1923 to 1987.

The view just above is from the station footbridge. There are four tracks in the station, the only place between Plymouth and Newton where fast trains can overtake stopping ones. The several buildings in the distance are other parts of the creamery, on both sides of Mill Leat, that are slated to be torn down or renovated. (From the shadows you can guess that my two pictures were taken hours apart.)

Here are some views of the town.

The River Dart, looking downstream. When the South Devon opened, SDR publicity suggested changing at Totnes for boats to Dartmouth. (The almost all-rail route via Paignton opened in 1864.) The right bank here is Vire Island, separated by Mill Leat, here called Mill Tail, which joins the river this side of the white buildings in the distance. Locals say that the island was brought here in 1974 by tugboat from the town of Vire in Normandy.

Fore Street, looking west. It becomes the High Street after passing through East Gate Arch and there entering the oldest part of the town.

Remains of Totnes Castle. It's quite a climb, and makes you realize why modern stairways have occasional landings. This does not.

View north from the top of the castle. Down below is the entrance from Castle Street. The creamery chimney marks the location of the station. From there, the track and up platform are visible to the left and the atmospheric buildings to the right. Further to the right, the distant railway curving to the left is the heritage South Devon Railway.